Can specialist retailers steal traffic from some of the biggest ecommerce brands in the UK? We discussed it over a drink or two.

The past six months or so saw a fair amount of conversation in the search community recently about three particular words; expertise, authority and trust. They are principles that are now firmly at the heart of what Google is trying to encourage with its new search guidelines, and concepts that the search engine believes are becoming increasingly important in the eyes of consumers.

It raises an interesting question – does this emphasis on expertise, authority and trust make it easier for smaller, niche retail brands to gain visibility over the digital ‘mega-marts’ that have dominated search for so long. Are we entering an era where it is better for brands to be masters of their craft, and to demonstrate that mastery, rather than the proverbial ‘jack of all trades’?

History tells us that expertise, authority and trust are just three of a plethora of factors that influence search engine rankings and when all is said and done, it will more often than not be the big, established brands that win the day. When it comes to search ranking, it has generally been that the size of the dog in the fight, rather than the size of the fight in the dog, is what prevails. Consumers trust big brands, they trust names that they can recognise, and they trust that those brands can deliver what they want, when they want it.

But are there ways in which the smaller specialists and more niche brands can overcome the power of those bigger brands?

We decided to test the theory in a market where there has been a surge in the number of retail brands entering the market, and a market where there was an interesting balance of smaller, specialist retailers competing against much larger brands and retailers, the UK beer market.

Why beer?

The UK beer market has seen something of a renaissance in the last few years, fuelled primarily by the growth of craft and specialty beers and a growing consumer demand for more varied tastes and flavours, as well as a growth in home-drinking. In 2015, the proportion of beer sold in the UK ‘off-trade’ overtook the proportion sold in pubs, bars and restaurants for the first time and in 2017, 53% of all beer in the UK was sold away from licenced premises (Brewers of Europe). The number of breweries also continues to grow. There were 2,430 active breweries in the UK in 2017, 97.5% of which were classed as microbreweries.

With this in mind, we felt that this was an industry where there was a very diverse range of brands competing for a similar type of audience. Whilst some of the mainstream retailers may naturally be focused on the more mainstream beer brands, it is noticeable how all of the major supermarket brands have increased their ranges of imported, specialty and craft drinks in recent years and that puts them in competition with some of the more niche brands.

We also believed that a diverse keyword set would also highlight where the smaller brands could generate visibility, and where the larger brands were perhaps missing some key elements to their search strategy.

Our keyword set spanned 4,302 keywords that collectively generate a monthly search volume of 836,600. These keywords covered generic keyword terms, brand terms (for the beers and breweries, not the retailers themselves), beer styles, beer regions and other defining characteristics.

What we were looking to determine was whether specialisms, expertise and a defined niche would be able to gain visibility in a market that is still dominated by those established mainstream retailers. So what did we find?

The smaller brands are gaining a foothold in the search market

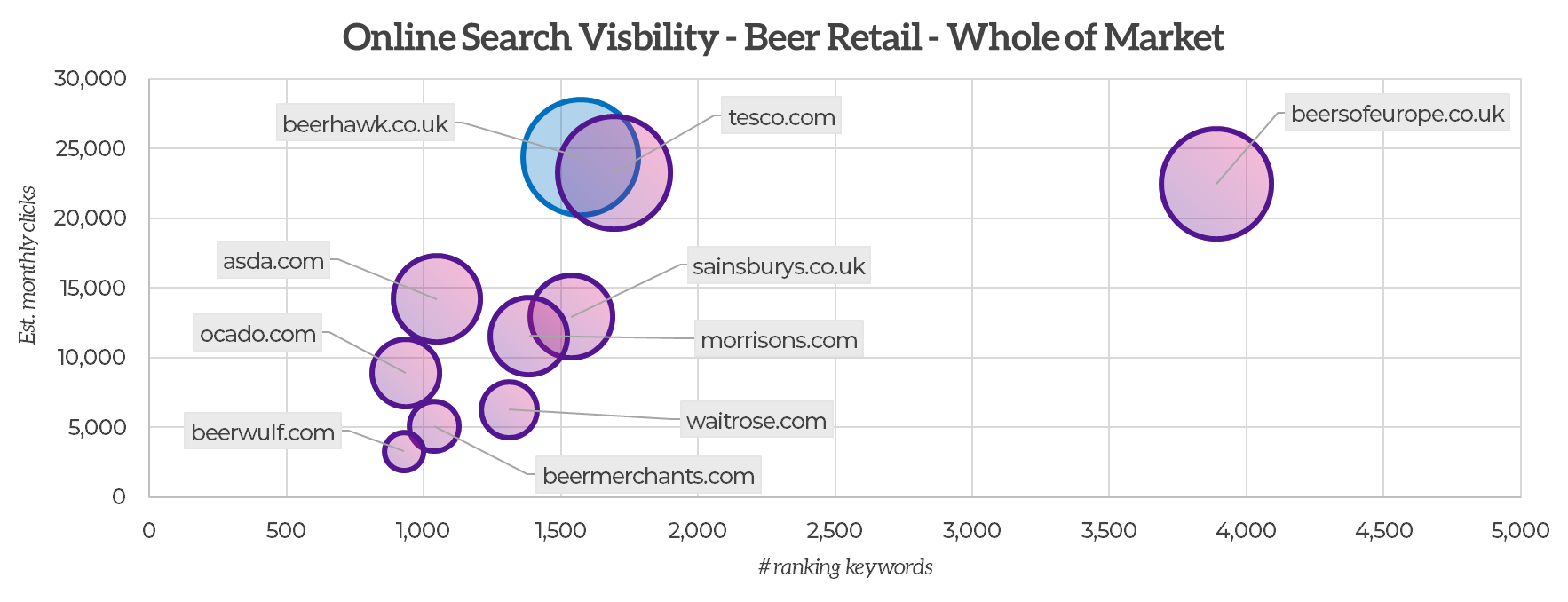

When we look at the whole of the off-trade retail market for beer in the UK, we see that many of the specialist brands are competing in the retail and ecommerce space. Of the ten most visible retailers, Beer Hawk is the most visible brand, ahead of Tesco and the third-placed brand, Beers of Europe.

Below these three brands is a cluster of mainstream supermarket brands, but we also find Beer Wulf and Beer Merchants taking a respectable level of traffic in the market.

Both Beers Hawk and Beers of Europe brands achieve this visibility partly due to ranking in first and second position respectively for the term “beer”, but this keyword term actually accounts for a relatively small proportion of the traffic that these brands generate from organic search. In the case of Beers of Europe, traffic from this keyword only accounts for around one-fifth of the brand’s overall traffic from organic search.

Beers of Europe is itself unique in the market in that it ranks for significantly more of the keywords in our analysis than any other leading retail brand, ranking for 90% of the 4,302 keywords we analysed. Looking deeper, the brand appears to have a solid approach to content and product categorisation, ranking for keywords based around product and brand names, product types, regions and flavours. This allows them to generate large volumes of traffic, and much more qualified traffic, from less competitive keyword terms. The brand generates just over 16,800 monthly visits (three quarters of its organic non-brand search traffic) from ‘non generic’ keyword terms and 48% of its traffic from keywords that have a search volume of less than 1,000.

For comparison, Tesco gets just 18% of its traffic from low-volume keywords, whereas Beer Hawk gets 23% of its organic traffic from keywords with less than 1,000 monthly searches.

Even excluding the speciality products, the niche retailers gain traffic

There is an argument to say that by including such a wide range of keywords that include very niche and specialist terms is essentially ‘rigging the deck’ to deliver the more favourable results to the niche brands. Supermarket brands do not have the level of interest that the niche brands have in the more specialist products – they simply need to stock a range that is large enough to cater for what is still a relatively small audience, without cannibalising sales of the mainstream brand beers that still form the bulk of their sales volume in this product area.

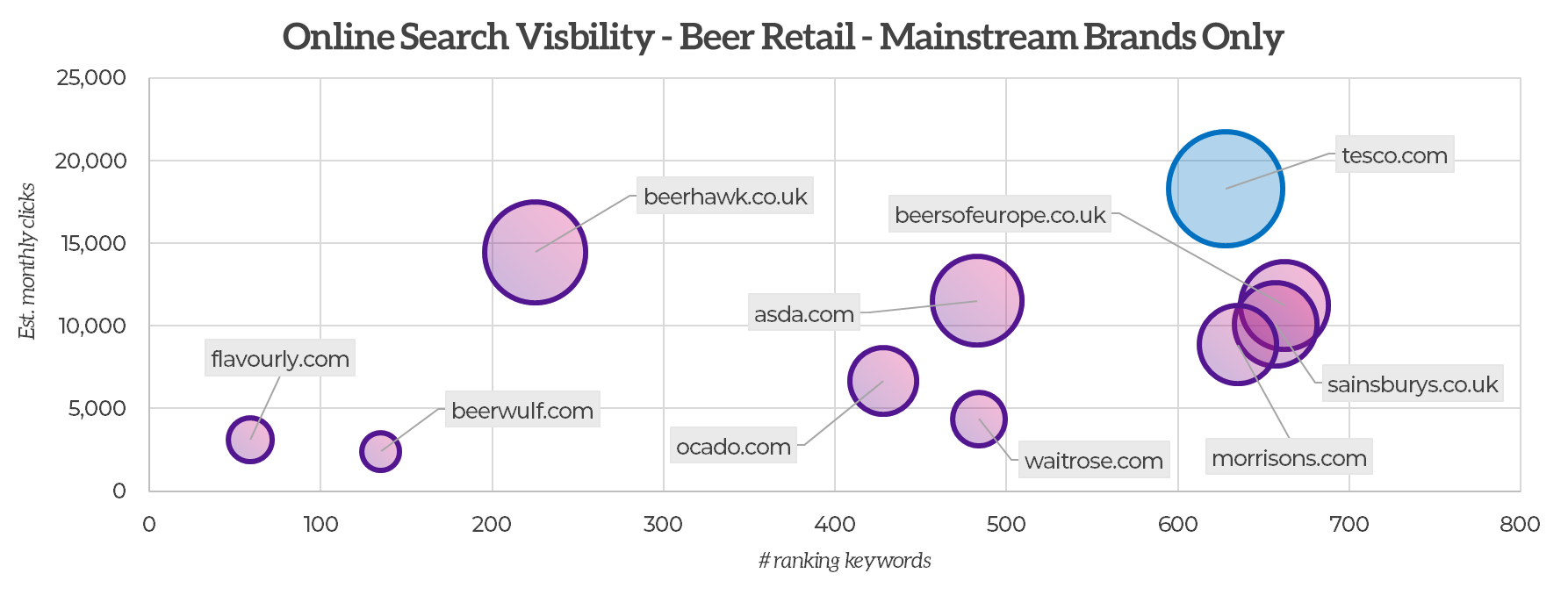

However, even if we remove those specialty keywords from our analysis and only focus on the mainstream and generic terms, we still see that some of the specialist brands continue to take significant levels of visibility.

Of course, we can see where many of the supermarket brands are focusing their efforts and generating traffic. Mainstream beer brands still account for the significant proportion of off-trade beer sales and this is where the supermarket brands are focusing their efforts. Tesco generates 70% of its organic non-brand traffic from the 821 mainstream keyword terms that we considered, whereas Asda and Sainsbury’s both rely on mainstream terms for 81% of their organic non-brand traffic.

But we do see that even on mainstream terms, some of the bigger ‘specialists’ can compete. Beer Hawk is the second most visible brand in the mainstream market, despite only ranking for just over a quarter of the keywords in the market, whilst Beers of Europe is the fourth biggest brand, generating roughly as much traffic in this keyword set than third-placed Asda.

Whilst these brands clearly generate much of their traffic from more specialist terms, there are clear signs that they are able to compete with the supermarket brands in the segments where those bigger brands should be strongest. So what are they doing right?

Specialist brands with specialist content reap the rewards

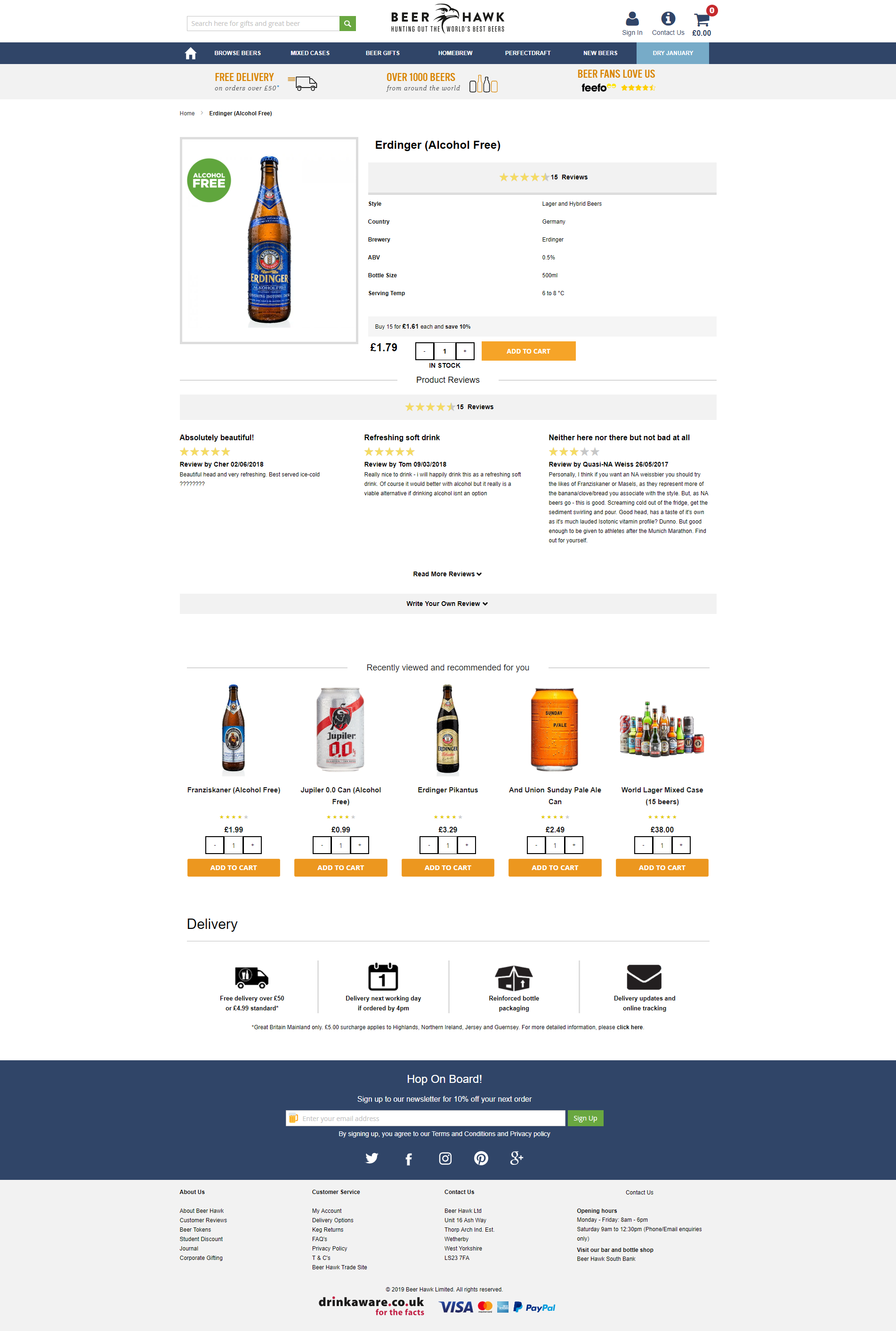

One thing that is striking when we start to look into the “why” behind these rankings is just how well the specialist brands present their content on their respective products and category pages, and it brings us back to that earlier point about expertise, authority and trust. The specialist brands that do perform well effectively provide main content and supplementary content to establish those three credentials to the user.

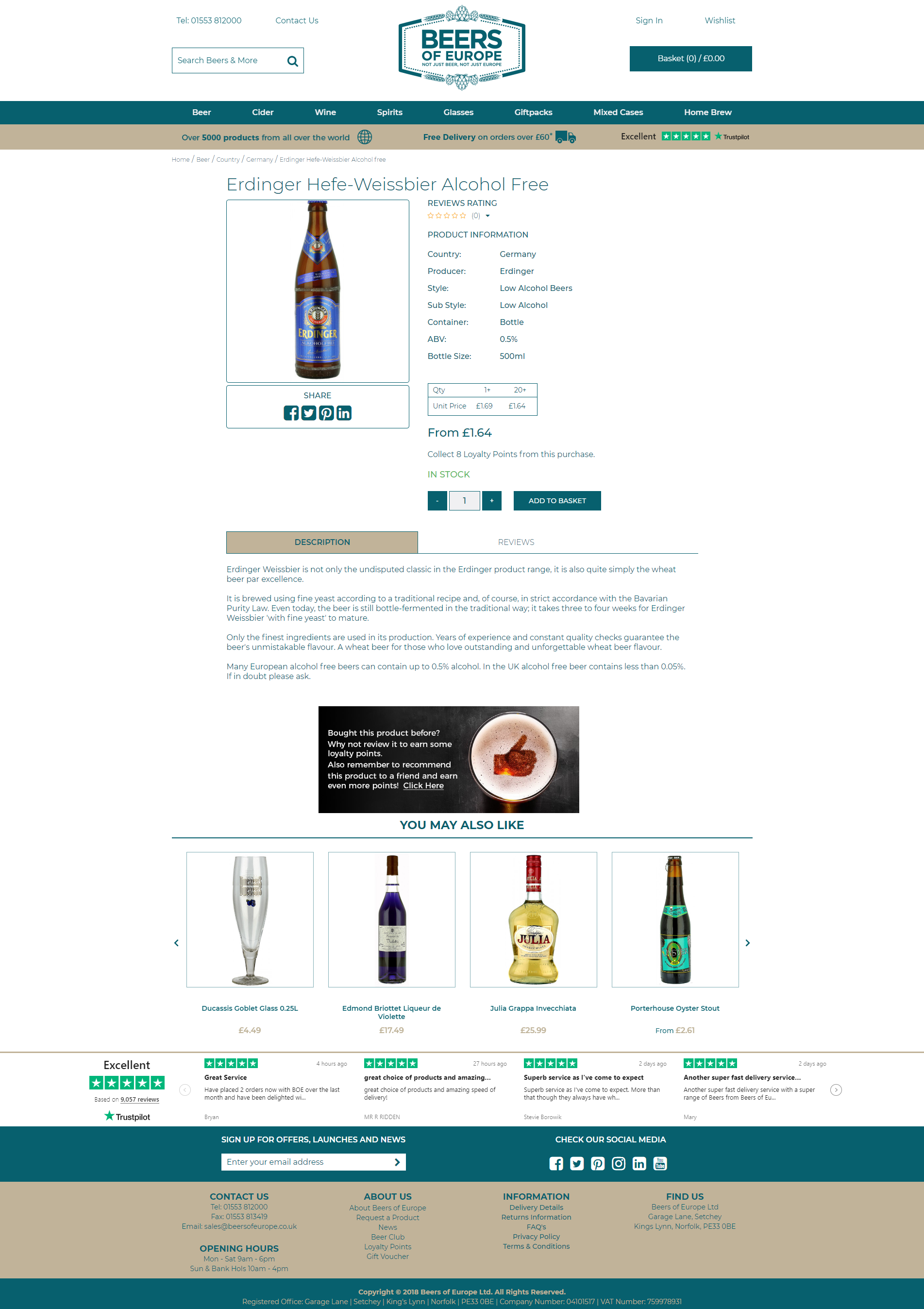

If we compare the product page for the same beer product across two of the leading specialist brands and the leading supermarket brands, we see some notable differences in approach.

Beer Hawk, for example, provides very prominent user reviews on both the brand and the product itself. These provide clear trust signals to the user and the user-generated content adds some authenticity to the reviews. The recommendation of alternative products is also good use of supplementary content, and is clearly marked.

Beers of Europe also provides credible reviews on its own service (via Trustpilot), and uses supplementary content to recommend alternative products, but it also provides engaging main content that clearly explains the product. There are detailed descriptions of each product that appear to have been produced by someone with genuine product knowledge and an understanding of what the audience is looking for, such as tasting notes. This is another quality trust signal for the user.

When we compare this to the leading supermarket brand, the page doesn’t quite convey the same levels of expertise. Whilst we have a lot of content here, much of it is relatively generic and uninspiring. There are no customer reviews, and much of the information is essentially a copy of specification list where many of the fields are incomplete or empty. This approach is very much contrary to Google’s recently updated Search Quality Evaluator guidelines.

What can we conclude from this analysis?

It is worth noting that we didn’t conduct this analysis specifically in the context of the Google EAT update of August 2018 but what this analysis does provide is a snapshot of the market and where brands are generating traffic from organic search. Using what we do know about good SEO practice, we can draw conclusions behind those rankings.

Firstly, it is clear that specialist brands can compete in niches where the search market has traditionally been dominated by bigger brands – they simply need to find the niche and the audience that works most effectively for them.

But they can also compete on mainstream terms by simply following the fundamentals of good search engine optimisation, user experience and ecommerce practice. Whilst this analysis is simply a small snapshot of one specific sector, there are signs that relatively new brands can have a disruptive effect on the market simply by adapting their search strategy to what both Google and their audiences are looking for.