Google updated its search quality evaluator guidelines last month, placing a greater focus on the “E-A-T” principles of expertise, authority and trust. Those new policies have already had a major impact in some key search markets. With major brands in some key niches losing visibility, we analysed at what it means for your search strategy.

Earlier this month, Google confirmed that it had deployed a ‘broad update’ across its search algorithm, in an update that it described as “one that would reward previously under-valued search results”, based on their content and authority.

Since then, we have seen some quite notable examples of how this update is working out in the real world, and it seems that a number of major brands in some very specific niches are seeing major losses in visibility.

Search Engine Roundtable, which first reported the update, found that regulated search markets appeared to be particularly vulnerable to the new update. Specifically, pages that Google categorises as “Your Money, Your Life” or “YMYL” pages (shopping and financial transaction pages, financial services, medical information, legal information, news and public information).

It tested 300 sites that had lost visibility, and found that just under 42% of those were in the health sector, with ecommerce (16%), business services (10%) and financial services and insurance (8.7%) also hit hard.

Major commercial brands lose organic visibility

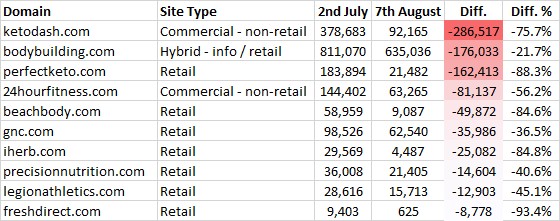

After looking at the search market since the update went live, Stickyeyes has noted that some sectors have been hit particularly hard in recent weeks, in both the UK and US. What our in-house analysis seems to show is that the update is affecting numerous markets, but one that demonstrates this shift perhaps most strikingly is the US sports supplement market.

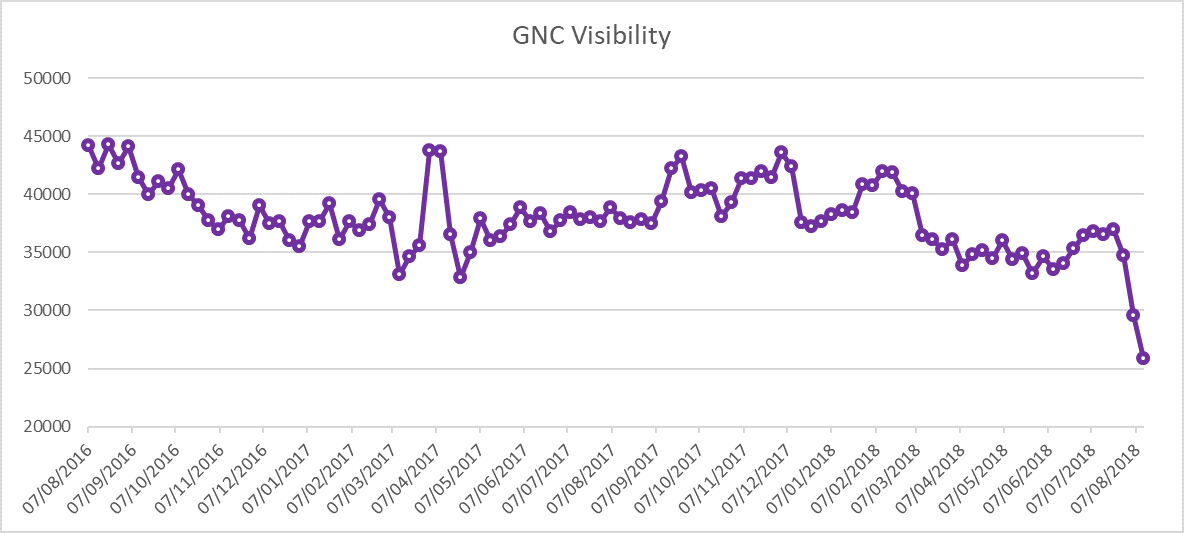

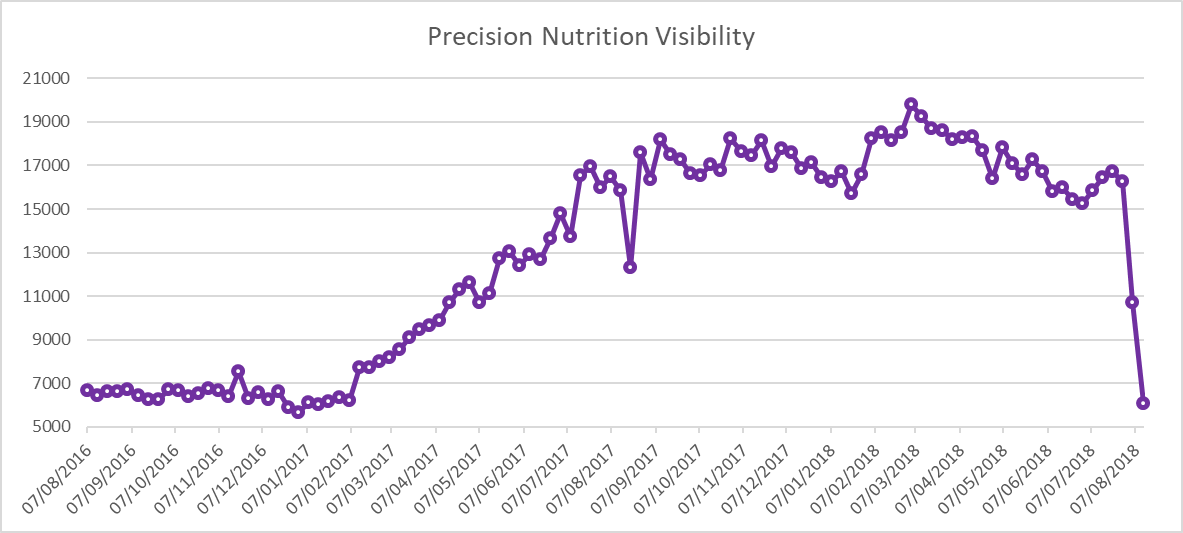

In some cases, commercial brands in this sector have lost almost all of their organic search visibility in just over the space of a month. What we see in the American sports supplement market is a number of leading retail brands, including one of the market-leaders in GNC, losing significant search rankings and expected traffic volumes.

Data from Searchmetrics tells a similar story, with GNC and Precision Nutrition both experiencing visibility drops between July and August.

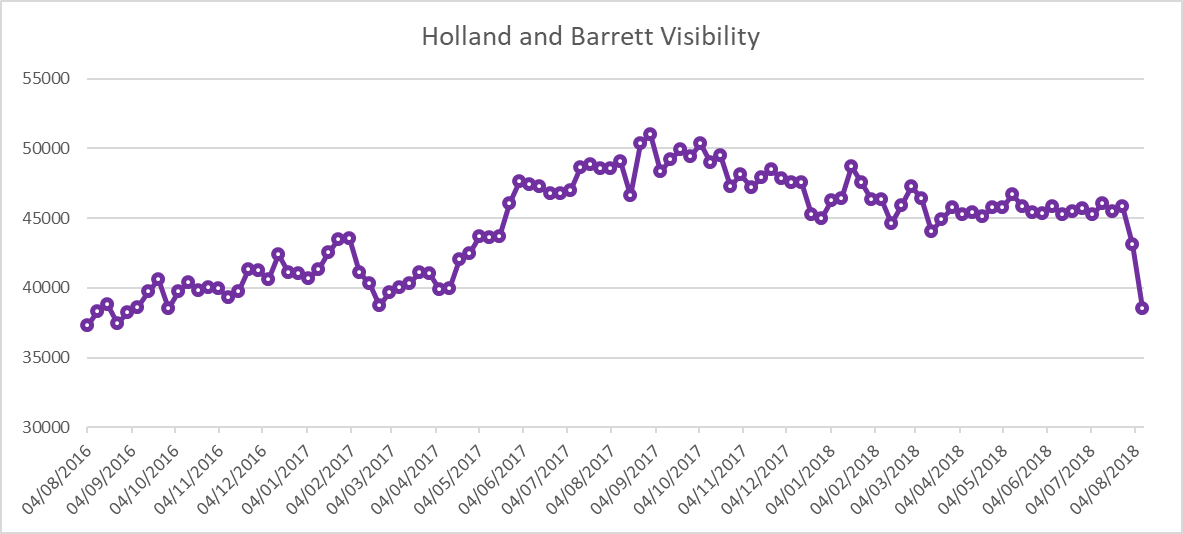

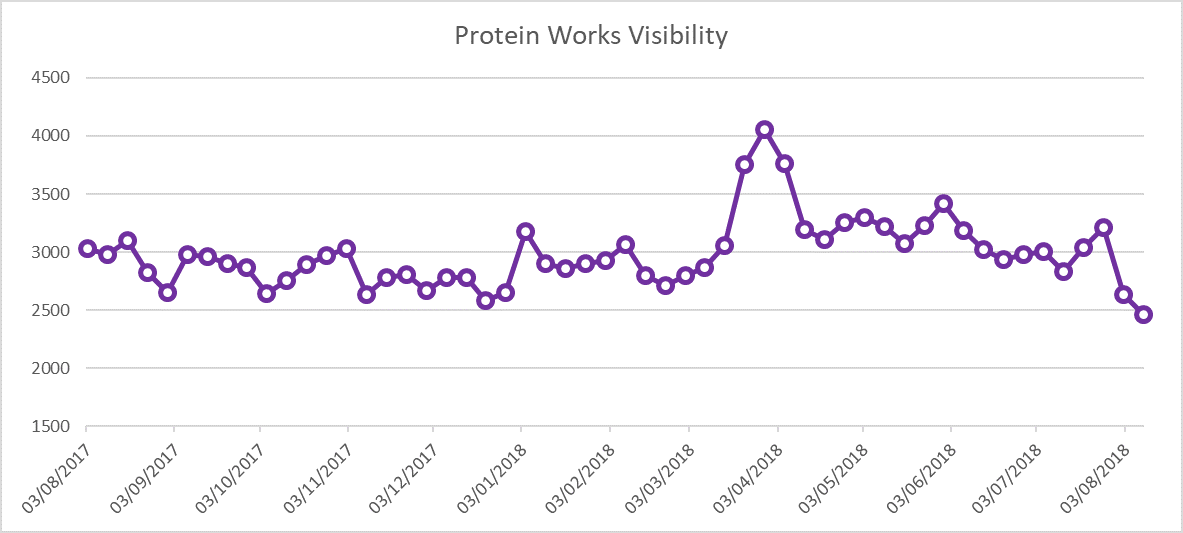

Looking at the UK market, we see that both Holland and Barratt and The Protein Works have also seen similar visibility drops.

So that seems to be an indication as to the “what” is happening, but a look at the brands that are replacing these domains at the top of the search rankings appears to give us a better indication as to the “why”.

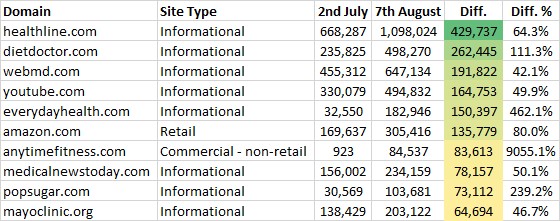

When we look at the brands that have seen significant gains, we see a heavy trend towards high authority informational sites. Healthline.com, Dietdoctor.com and WebMD are the big winners here.

These are all sites that cover the topic of sports nutritional supplements with a degree of authority, impartiality and trust that many commercial brands, despite the best of intentions, would struggle to replicate purely because of the commercial priorities that they have.

A broad update, with broad impact

It’s important to remember that this wasn’t a sector-specific algorithm update; this update is a global update that affects the whole algorithm, and there are numerous examples of brands, particularly in the YMYL sector, losing and gaining visibility on or around the first week in August.

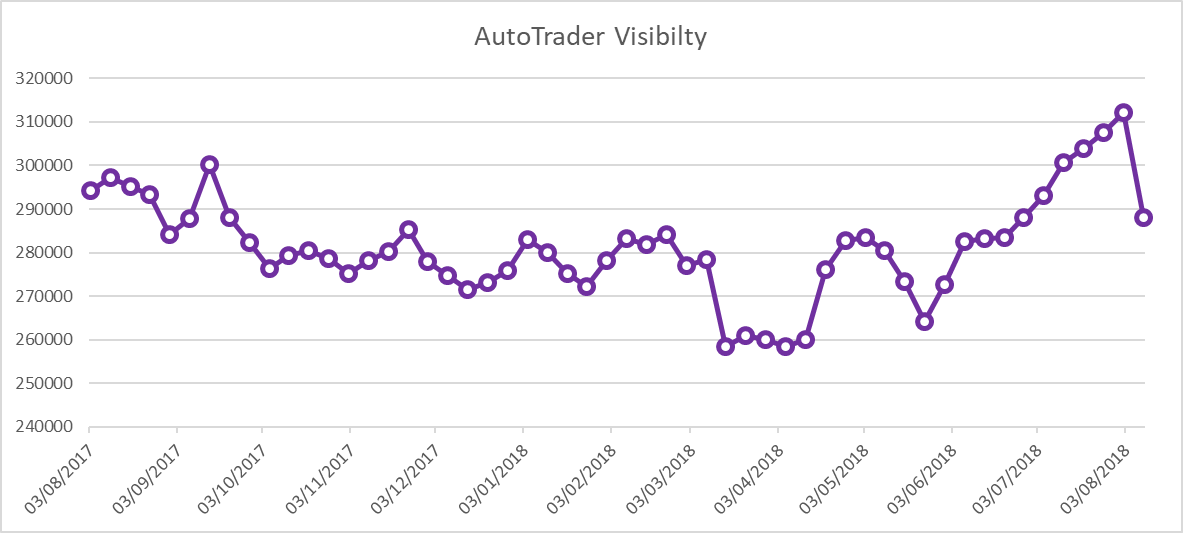

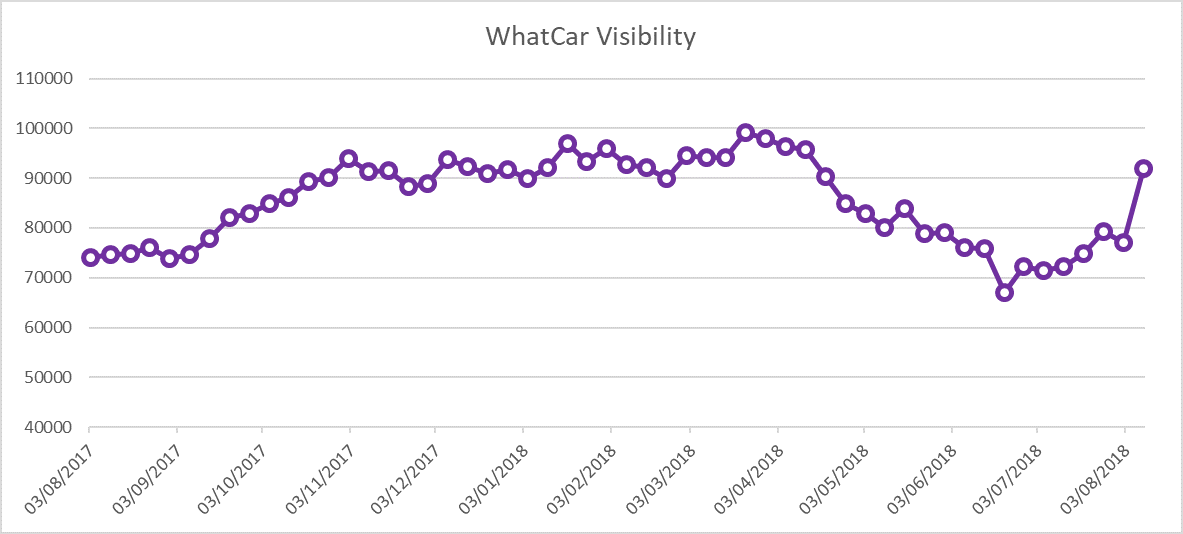

In the automotive sector, Autotrader.co.uk has seen a decline whilst, at the same time, the consumer publication whatcar.co.uk saw its visibility grow.

So does that mean that commercial brands are being forced out of the organic search results? Well, not necessarily. But it is important that they understand precisely what Google is trying to do with these updates by understanding how and why it has updated its “E-A-T” policies.

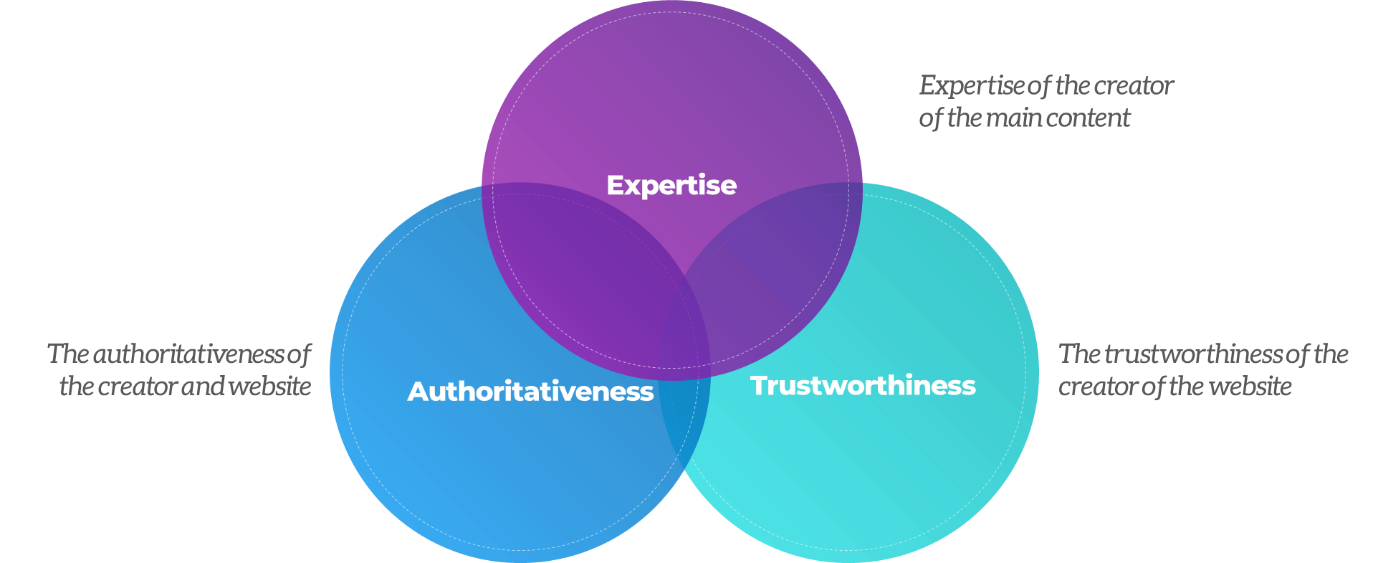

Understanding the E-A-T principles

Google’s E-A-T principles judge the content of a given page on three key measures of quality; expertise, authority and trustworthiness.

This process for measuring content has been with us for a while, but Google updated the guidelines that it issues to its Search Quality Evaluators on 20 July 2018. The changes reflect the fact that more and more brands and publishers are producing content, all to varying standards, and that unduly relying on traditional measures of authority such as brand reputation and domain authority were far too simplistic a measure to determine the quality of a search result.

Google said that this algorithm update was about “uplifting those domains and pages that were previously being under-valued”, and these sorts of results provide some strong indications as to what Google considers to be that “value”. It wants to see quality, researched and impartial content that consumers (and Google’s users) can be confident in trusting. In particular, Google makes it clear in its guidelines that pages that fall within the YMYL category need to be subjected to greater scrutiny:

We have very high Page Quality rating standards for YMYL pages because low quality YMYL pages could potentially negatively impact users’ happiness, health, financial stability, or safety.

We can see that there is now a much greater emphasis being placed on the credentials of the author or publisher, how impartial that author or publisher is, how established they are, and how they are trusted within their respective audience communities.

Brands need to respond quickly to protect their organic visibility

It is important to remember that no brands have been “penalised” as a result of either this update or the change in Search Evaluator guidelines. Brands may have seen their rankings fall following these changes, but this is simply an adjustment to the way that Google judges site quality, rather than a specific penalty that requires a specific action to resolve.

Instead, Google is simply raising the bar on the standard of content that it wants to see from publishers and what it wants to provide to its users. For some time now the ‘barrier to entry’ when it comes to being a content publisher and an “expert” has been relatively low, and so-called “me too” content (content that has been produced purely to fulfil an SEO need) isn’t going to cut it. Instead, brands need to think more like publishers and look at the content that they produce with a much more editorially critical eye.

This probably all sounds very familiar – create really good content because that’s what Google wants – and that’s because it is familiar. The difference in many respects is that Google is not only raising its expectations of what content you should be producing and how you should be adding value, but it is also taking a more critical eye on how that quality and value is portrayed.

A good example of this is looking at how the ‘expertise’ of an author is portrayed.

Let’s go back to the topic of sports supplements and specifically, this line in the Search Quality Evaluator guidelines:

“High E-A-T information pages on scientific topics should be produced by people or organisations with appropriate scientific expertise and represent well-established scientific consensus on issues where such consensus exists”.

Now, at the time of writing, this is the highest-ranking UK retail result for the search query “what is protein?”. It was found somewhere in the middle of page four.

As a piece of content, it’s well written (albeit somewhat sales-focused) and it answers the search query. But can we objectively say that it meets that search evaluator guidelines? Probably not, and perhaps the biggest reason why is because we have no idea who actually wrote that content. There is no author information, no profile of the writer and, other than knowing that the writer has some form of connection with the retailer, we don’t know if they are a qualified dietitian, a medical professional, a personal trainer, or someone with absolutely no understanding of protein and how it affects the body. That makes it extremely hard for Google to determine whether this is content that we should trust.

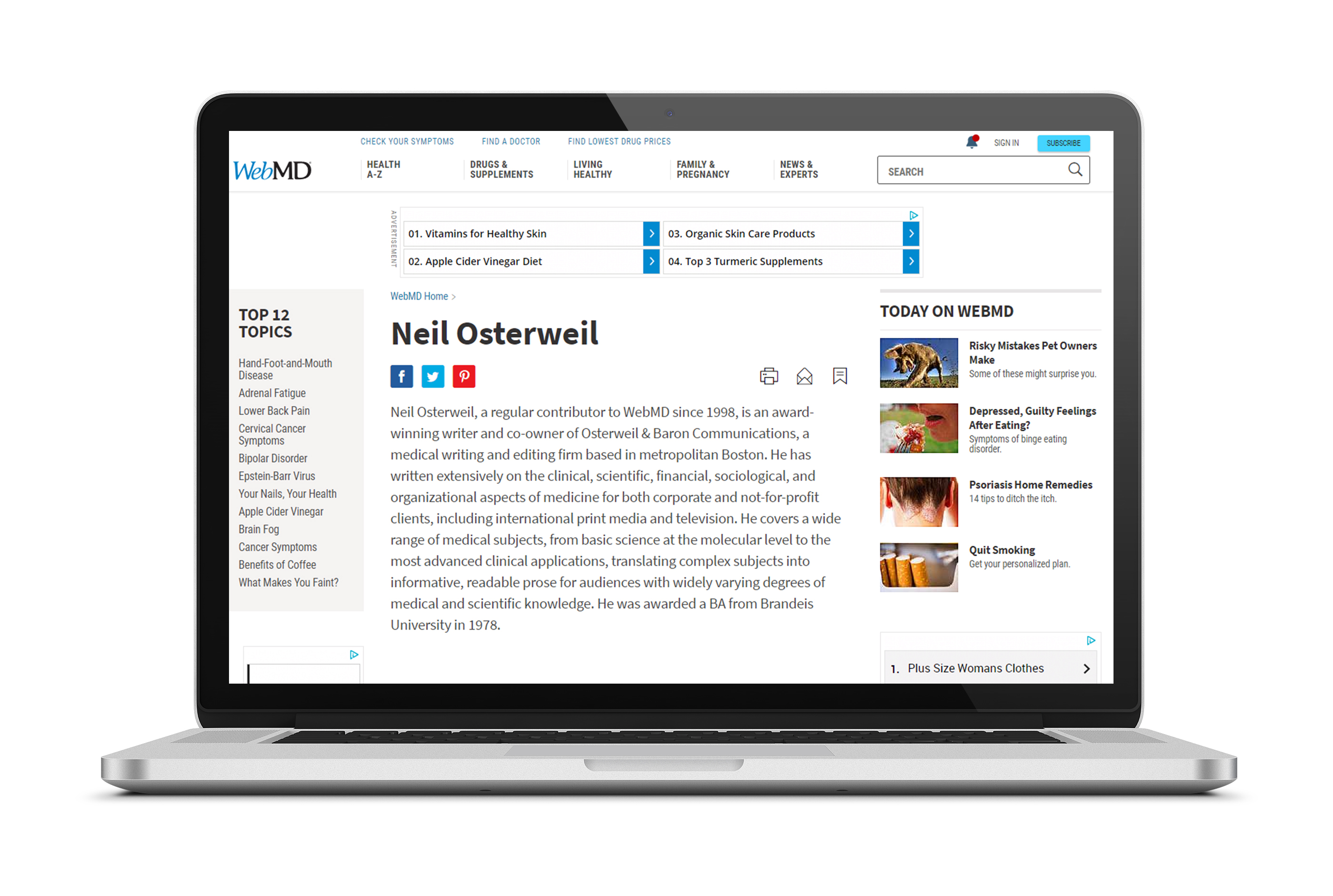

Compare this to the result provided by WebMD, which ranks in fourth position for the same search query. The article makes it clear that the author for the piece is Neil Osterweil, and it provides a link through to his profile page:

This to a search user, and to a search engine, is a clear indication that the writer is clearly an expert in his subject, and is someone who a reader should trust. We can see his educational background, his career background and his experience. This is a clear trust signal.

Of course, we don’t all work in highly regulated environments where academic credentials are necessarily required to be considered an expert on our respective subjects, but we can still demonstrate our authority on our subject matters.

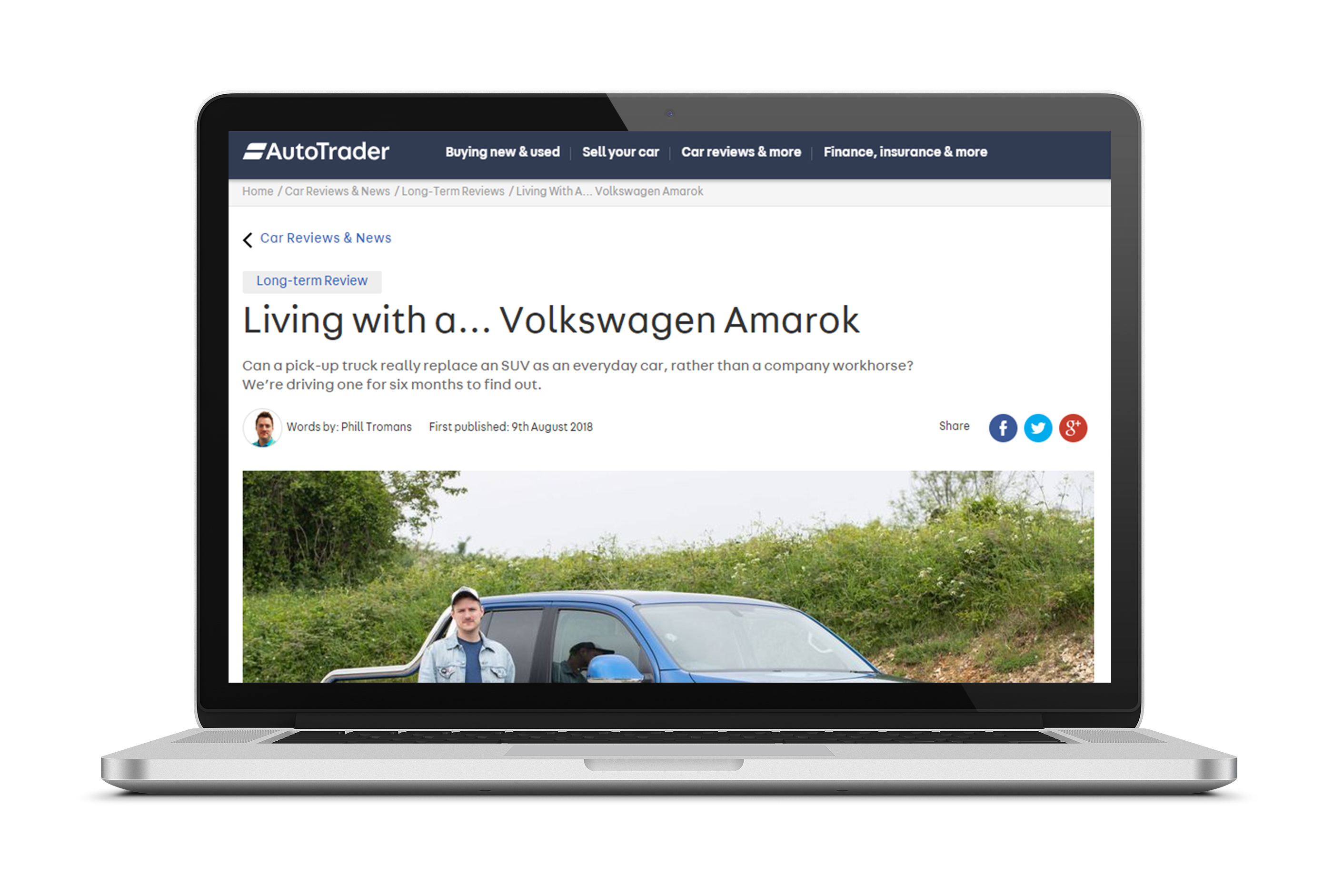

Take this example from Autotrader – a review of the Volkswagen Amarok, written by Phill Tromans and published on the website of one of the most iconic brands in the British automotive industry.

But unfortunately, the user landing on this page knows little about Phill Tromans, other than that he knows something about the VW Amarok. For all we know, Phil could be a long-time owner of a VW Amarok with lots of valuable insight that comes from personal experience with the product, but we don’t know for sure. He could be an established motoring journalist with decades of experience and a long list of awards under his belt, or he could equally be a work experience intern. This is, after all, the internet; people are not always who they seem.

What’s missing is an author profile (ideally marked up with the relevant schema) where we can find out more – where we can learn about who he is, his experience and how long he has been writing for the publication. There’s no link to other articles that he has authored – how do we know whether he has a tendency to prefer one car to another? We’re not suggesting that he does, and perhaps we’re more cynical than the average reader, but its information that’s missing when it could very easily be right there in front of both us and the Google Search Quality Evaluators.

So we just need author pages?

Google has always been, in public at least, very protective of its audience and the search results that it puts to them. These algorithm changes, and the updates to the search guidelines, are about ensuring that it continues to return search results that its audiences can trust, particularly in the era of misinformation and “fake news”.

The examples here are clearly snapshots of how a small sample of websites compare to the standards set in the updated search guidelines and they represent just one of a myriad of potential ranking factors, but they do act to highlight how a manual process of search quality evaluation may judge particular pages on the grounds of expertise, authority and trust.

These guidelines put a spotlight on particular aspects of your SEM strategy. They put a spotlight on factors such as brand and reputation. Brands may take a renewed look at how they focus on developing their brand reputation and authority to climb back up the generic search results. They may even focus more on how they can use their brand authority to generate more brand traffic to mitigate the loss in generic keyword traffic – if a brand can itself become an authority in the niche, it may reduce their reliance on generic search activity.

It also puts a light on their content strategy, and how the content that they produce engages users at each stage of the customer journey (our free Complete Content guide addresses this in more detail). We may see brands, particularly in the YMYL sector, invest heavily in highly authoritative writers and contributors, on independent researchers and prominent influencers to add that level of gravitas and trust to their content. A recommendation from a respected dietician or nutritionist represents a much stronger and convincing voice on the issue of sports supplements than a blog produced by an anonymous blogger.

It will invariably prompt brands to look at their biddable media strategy. If ecommerce brands are being effectively ‘locked out’ of the high ranking organic positions due to the strength and authority of information sites, some brands will inevitably turn to paid channels to cover the shortfall.

But above all, remember that Google hasn’t fundamentally changed what it is looking for when it comes to the search results.

There’s no “fix” for pages that may perform less well other than to remain focused on building great content. Over time, it may be that your content may rise relative to other pages.

— Google SearchLiaison (@searchliaison) March 12, 2018

It has always wanted quality content that users can trust. But in an era when it is becoming harder and harder for users to decide what they can and can’t trust, it is simply raising the bar on the standards that it sets. When Google gives advice to “remain focused on building great content”, that remains the right course of action. The only difference is that you need to ensure that your content isn’t just “great”, it’s something that people can rely on.

Is Google being a bit over-zealous here?

The changes we are seeing here are certainly profound, although it is not the first time we have seen something like this; there have been previous updates that have seen commercial brands displaced by informational pages across similar sectors that we have seen changes in here.

But even though Google is clearly focused on the YMYL sector, there is a valid argument that says that the seismic ranking changes that we have seen here may have been more severe than necessary. Whey protein is, in many respects, a grocery product and most consumer-facing products do not need a degree and a list of impressive credentials to be able to understand them or to be qualified enough to discuss them. There is a danger that by doing this Google is actively dis-incentivising brands from investing in that quality content that it insists they should be doing. Raising the bar is one thing, but raising it beyond the reach of all but the biggest brands may have unintended consequences.

In the coming months, search results may start to normalise as Google reviews the impact of these changes. Many of the brands that have lost out across all sectors have legitimate right to rank in the positions that they have fallen from. It wouldn’t at all be surprising to see many of these brands re-appear in the search results over the course of the next few weeks and months.